Mark C. Samples | Musicologist

“…ear-opening and

wide-ranging…”

—John Covach, Director, University of Rochester Institute for Popular Music, Professor of Theory, Eastman School of Music

Solie Award-Winner

For Outstanding Collection of Essays, awarded by the American Musicological Society.

About Mark

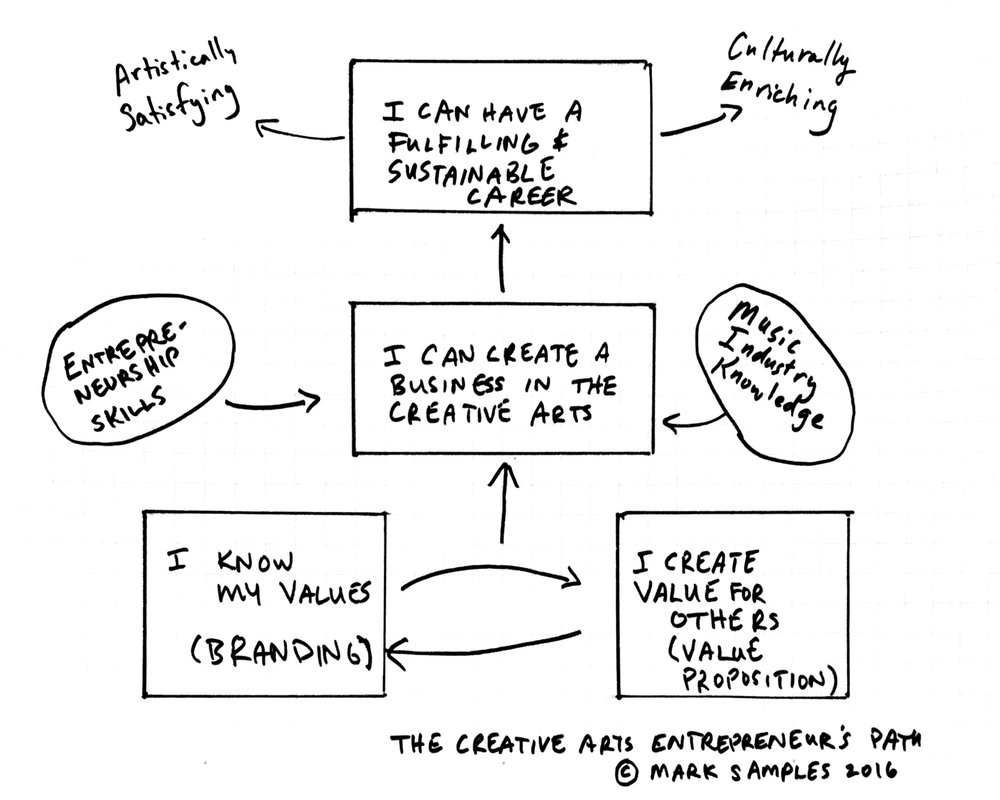

Dr. Mark Samples is a musicologist who studies how practices of promotion (branding, marketing, advertising) influence the cultural history of music in the United States. He also teaches entrepreneurship strategies to professional musicians across the country. He is an Associate Professor of Music at Central Washington University.

Every creative has felt it—the frustration of starting strong on a project, only to fizzle out halfway through. The ideas dry up, the momentum disappears, and you’re left wondering what went wrong.

The truth is, most of us approach creativity the wrong way. We rely on fleeting inspiration or bursts of motivation, hoping they’ll carry us through.

But the creatives who achieve mastery—those who produce consistently for years—don’t rely on chance. They use systems.

Let’s call it a Creative Flywheel.

In the early 1970s, Stevie Wonder was already a star.

He was a child prodigy, at that point the youngest artist ever to top the Billboard Hot 100 (“Fingertips Pt. 2”). He had already recorded a string of hits in the Motown style: “Uptight,” “For Once in My Life,” and My Cherie Amour.” He had started taking ownership of his sound by self-producing his record, “Signed, Sealed, Delivered,” in 1970.

In other words, he was twenty years old and already a paragon of the Motown pop sound.

But Wonder didn’t rest on his successes. He was hungry for something more.

He wanted to create music that truly reflected his artistic vision—something groundbreaking.

Enter two unlikely collaborators: Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil, a pair of audio engineers who were tinkering with a hulking, mysterious machine called TONTO (The Original New Timbral Orchestra).

Writer Benjamin Nugent, in a 2013 essay for The New York Times, described how he had what seemed like an idyllic writer’s life in graduate school.

No wi-fi. No diversions. Lots of snow. It was like he was a writer from another time.

But he found something surprising.

His complete devotion to his writing at the sacrifice of all other diversions actually poisoned his writing.

Confused. Dazed. Scatterbrained.

It can often feel frustrating to make up your mind to focus, but to feel unable to do so.

To set down a path of focus—to write a song, practice our instrument, work on a design—only to be offered a gleaming off-ramp in the form of a distraction from our phone.

It even happens to people trying to write a newsletter about focusing. My phone has buzzed 3 times since I started writing this newsletter.

Each notification from our phones is part of a habit-reward loop that promises a potential dopamine release for our brains.

We know that there is a war going on in the marketplace, and that our attention is the ultimate prize. Tech companies, advertising companies, even nonprofits and other creatives. All want to win the next second of our attention.

But I want to invite you to a different path. Now is the best time to disengage from our distracted networks of notifications and reengage your focus on what really matters.

This holiday season, make a plan to practice building the skill of focus in your creative life.

I had the opportunity to write music for RealTruck, Inc., the U.S.’s top seller of truck accessories.

The goal of the project was to create a 2-minute brand anthem that can be used across multiple campaigns (TV, web, social, etc.) and multiple years. To create the soundtrack of RealTruck’s brand.

After the project was over, I scribbled down “micro lessons.”

Bite-sized lessons of everything I want to remember for the next time I do a project like this.

Reply with a number and I’ll break it down in an essay or a comment.

Be alert for creativity to strike in the midst of the mundane. Even an unexpected blank page can hold the beginning of your next masterpiece.

You don’t have to be working in a cabin in the woods to have creative insights. You don’t have to be a hermit, or to wake up before sunrise and meditate.

You don’t even have to be doing something creative.

In fact, creative insights sometimes strike in the midst.

In the midst of cleaning your kitchen. In the midst of driving to work. In the midst of formatting TPS reports.

JRR Tolkien tells a cool story about how he started writing The Hobbit. Tolkien wrote some of the most beloved fantasy novels of the twentieth century. But, like me, in his day job he was a university professor.

In a BBC interview in 1968, he recalls how the first line of his book The Hobbit came to him.

When you are trying to develop a creative skill, small improvements every day beat sporadic epic bursts. Every time.

Imagine two creatives, Oliver and Amelia. Both are music producers at the beginning of their careers. Both have visions of really making it—working with interesting artists, producing music they can be proud of, and supporting themselves through their creative work.

In order to have the careers they want, they both know that they need to continuously improve their skills. They need to learn new production techniques, become better songwriters, improve their mixing skills.

The list of improvements seems endless. They feel a deep skill deficit. Like a chasm that stands between them and the career that they want.

Oliver sets out to improve his skills. He works in bursts, but sporadically. Marathon sessions on weekends and late at night. After a session, he feels burnt out, and then it takes days or even a week before he can muster up the energy for another session.

In creative pursuits, quality will come as a result of quantity. Get intelligent reps in your field and share your work before you think you’re ready.

Writer Ryan Holiday said in an interview that he doesn’t put much stock in the "quality over quantity" excuse when creating.

You know the one. You say you want to line everything up first. To get everything ready so that it’s just right before releasing it to the world.

You say you want to painstakingly get everything right before you release your masterpiece.

Whenever you meet someone interesting, think to yourself—who do I know that this person should be connected to?

Write an email introducing your two friends. Say something about why you think they should be connected. Something like:

“Hey Rob, meet Jessica. Jessica fronts a rad Seattle band called Deep Sea Diver. They just released a new music video. Jessica, this is Rob. Rob has played the violin on probably some of your favorite records, from Sufjan Stevens to Bon Iver and even Taylor Swift. He just played with Sara Bareilles at the Kennedy center in a series of concerts celebrating her career and songbook. Y’all are both awesome, and I thought you should know each other!”

More from Mark